Introduction:

Establishing a Sense of Place

I grew up in a small ranch-style house, painted white, south facing, with a large living room window that draws in streams of light. It’s settled on three acres of land in southern Maine, a once-rural region that has for the most part turned into suburbs (increasingly so during my lifetime). When my parents bought the house it was surrounded by fields and woods, bordered by a body of water aptly named the Little River. Because my parents could only afford to purchase three acres, in the early 1990s bulldozers tore up our sledding hills and our “tag” trees and put in a housing development.

Even though the earth was cut, the houses were built, and the landscape changed, my two older sisters and I continued to play outside in all seasons. We built forts and collected fireflies, picked lilacs and ran through puddles. Our brown barn housed a collection of critters including a pony named Poncho and a goat named Quentin.

It was not until the summer entering my junior year of high school when I began to process my family’s deep connection to place. I saw an ad in a local paper recruiting teenagers to join the Presumpscot River Youth Conservation Corps for a seasonal job. The Little River is a tributary of the larger Presumpscot, which is accessed just a few miles away from my house. I fired off an application for the PRYCC, landed the position, and began to incorporate terms like “watershed” and “riprap” into my vocabulary.

The crew was led by a college student and consisted of five members. We moved mulch and rocks to reinforce trails and support banks, created infiltration steps, pounded rebar, planted trees, and spray-painted storm drains. We dug ditches and hammered nails, built bridges, and constructed canoe launches. The work was hard and I soon gained a newfound appreciation for lunch and water breaks. It was also fun—we would come up with riddles and jokes and trivia to pass the time, we got to take dips in the river, and sometimes when we were working on private land the homeowners would treat us with ice cream sandwiches.

I began to feel pride in the work I undertook. It was tangible, noticeable, and something I could return to throughout the year. I continued my role with the PRYCC the next summer before leaving for college, and four years later decided to move west to join the Montana Conservation Corps for a six-month position. Being a trail crewmember with the MCC soon became the biggest challenge I had ever attempted, as I learned how to camp in the backcountry, pound rocks with sledgehammers, and cut Ponderosa Pine with two-man crosscut saws. In other words, the PRYCC was the minor leagues and the MCC was the majors.

Because it was an AmeriCorps program we had little booklets that provided prompts for crew discussions, all based upon this concept of “Place”. We hailed from different parts of the country—Maine, Florida, Ohio, Indiana, and Montana—and brought varying perspectives to issues ranging from civic engagement to wolf populations. Around campfires and atop mountains we hashed out ideas, contemplated theories, and tried to make sense of not only our present work but also our future ideals.

For years I had daydreamed of the West, falling into the classic cliché of belief that once I got out of New England and found those sweeping hills and valleys with ever-changing skies my life would forever alter for the better. I looked at pictures from my parents’ photo albums chronicling the many spirited years they lived on the opposite side of the country. I attached myself to the words of Norman Maclean and Ivan Doig, Terry Tempest Williams and Jack Kerouac. The West was wild and uninhabited; it was full of possibility and promise. When I finally found myself walking alongside Montana’s Big Blackfoot River and boating on Idaho’s River of No Return and trekking through California’s redwood forests I felt inspired, transfixed, and excited. I might as well have been in foreign countries.

Yet, the wonder wore off after a couple of months. After the initial excitement of being elsewhere my mind drifted back to the small ranch-style house in southern Maine and the river that flows by it with all its sentiment and memories. Try as I might, I couldn’t leave my roots behind, couldn’t adopt a new persona or even apply for a new driver’s license, clutching onto my plastic Maine identity card with pride. I even moved to the mecca of all things cool, Portland, Oregon, but I felt like a poser, a fraud. I wasn’t a cowgirl or a stoner or an urban hipster. I was certainly a dreamer but one who liked to do so from the comfort of familiar surroundings, someone inextricably tied to the land and water of her youth by something great and yet unseen—a force that accumulated momentum and strength with each passing year.

So I bought a ticket home. I need to find out why I care so much about this place. I have to look below the surface, to dig deep into the history of the Presumpscot to translate the meaning of the whispers and winds that continually pull me back to this small corner of the world.

It is my hope that in telling the story of my backyard river it will encourage others to look at their own small rivers and woods and streams with new eyes. There are hidden tales among the rocks and leaves and you might find, as I have, that those stories are beckoning for some recognition.

It Starts at Sebago

There are limits to what one can learn by standing on the shore of a river. While I’ve often kayaked and canoed the section of the Presumpscot that is closest to my house, I’ve never paddled the whole length of the river, which originates at Sebago Lake Basin in Standish and continues down through the towns of Windham, Gorham, Westbrook, Portland, and Falmouth. I decide that after all these years I need to physically experience the river from start to finish by paddling from its headwaters to its outlet at the sea.

Because I’ll bring along photo and video equipment to document the process I choose to take our family’s spacious Coleman canoe, rather than a narrow kayak. The canoe is a beast to carry so I also bring along my partner Kyle who is a burly 6’1’’, an avid fisherman, a former Boy Scout, and a media guru. His help with the technical aspects of the trip will be especially important for the many portages we’ll have to make, as the river has eight dams. Having another person to steady the canoe and assist with navigation means that I’ll have more time to focus on filming and observing. He will also be good company.

Kyle has long brown hair that falls past his shoulders. He recently told me that he’ll never cut it again as a symbolic gesture to “the man.” He’s someone who revels in the spotlight on stage as an actor and a comedian, but also enjoys the solitude and stillness of nature—a gentle giant. We both attended Gorham High School; Kyle grew up in Standish and is very familiar with Sebago Lake. He hasn’t spent much time on the Presumpscot so we’ll be exploring new places together.

The Presumpscot is only 25.8 miles long, but in that short distance it drops an impressive two hundred and seventy feet. Its name originates from the local Native American word of the Abenaki tribe meaning "many falls" or "many rough places" because prior to dam construction there were at least twelve falls. The trip could potentially be made in two days but we decide to stretch it out over four days, spacing them throughout August and September so that we can watch the surrounding landscape change as summer gives way to fall.

It all begins on a muggy morning in August as we pack a cooler with water and snacks, load our canoe on top of my dad’s utility van, strap it down, and head to the dock just below White’s Bridge in Standish where Sebago’s basin begins. Sporting bandanas and life jackets, Kyle and I set off of our journey à la Lewis and Clark (or so it seems at the time), armed with the most up-to-date guidebook about the Presumpscot River from 1994, some Google Maps images, and a general sense of direction.

Sebago is Maine’s deepest lake at over three hundred feet with a surface area of approximately 28,771 acres. It is the primary water supply for the Portland Water District whose service extends to the Greater Portland area, which contains 15% of Maine’s population. The lake is also a popular summertime destination for its sweeping panoramas dotted by the state’s beloved pine tree. Loons drift and dip atop clear blue water that softens as the sun recedes to calm pastels of gold, pink, and orange.

On days like today the lake buzzes with a flurry of activity as families enjoy the modern comforts of camp life, including a wide array of recreational toys. Kids buckle into water skis, rise upon wobbly legs, and proudly command, “Hit it!” as their parents oblige and zip motorboats across the water. Music blares from stereos amid sunbathing, drinking, and socializing. The lake is a getaway, a retreat, and a place for relaxation, yet still supported with conveniences not found in the backcountry (including vehicles, fans, and refrigerators). Its close proximity to Portland—about a 45-minute to one-hour drive—provides efficient access to campgrounds, seasonal rentals, and a state park.

Although manageable and scenic, while paddling down the basin in a canoe I become eager to arrive at the river where there will be less commotion, fewer people, and calmer water. We have to wait out the choppy waves caused by motorboats by turning the canoe parallel to whichever direction the waves come from until the movement subsides.

Kyle and I make our way south, spotting the first portage at the Head Dam after about forty-five minutes from the start of our trip. Pulling out to the right of the dam proves easy enough and we only have to drag the canoe about fifty feet across a dirt road and down a bank, albeit scratching our legs on thorns and thistles. We stretch our limbs and prepare for the next section, which will require balance and concentration—a voyage down the Eel Weir Canal.

Manmade Container

We decide to take this route because the first part of the Presumpscot below the basin is too shallow for a successful canoe trip, although it is accessed on Route 35 and is an extremely popular place for fly fishermen. Canoeing in the canal feels strange, mainly because of how contained its boundaries are. Unlike a river, which has twists and turns and diverse scenery, this section is a straight shot. It was originally part of the larger Cumberland and Oxford Canal, which stretched from Long Lake in Harrison all the way down to the Fore River in Portland.

Eel Weir Canal construction started in 1828 when Irish laborers hand-dug the ditches using shovels. I can only imagine the sweat on the brows of the laborers who dug into the earth here. I’ve done a fair share of work with Pulaskis and pick-axes, but nothing anywhere as extensive as this channel. When it opened in 1830 the canal was used for hauling logs and shipping freight. It was a slow method of transportation and was unavailable for use in the winter because the water froze, but it did generate increased activity between the coastal and lakes communities. Financially, it never made a profit and it closed as a business venture by 1872.

As we approach our next pullout spot Kyle advises, “Get ready to paddle for your life if we have trouble.” It’s an accurate statement, as canoeists and swimmers have drowned here due to the steepness of the banks and the great depth of the water. We manage to steer the canoe to the side but without stairs or a gradual incline it’s difficult to climb onto the bank. I grab a handful of tall grass, sliding my fingers down into the dirt to get a firm grip on the land before I heave my body up. Suddenly, I hear a buzzing noise. I look down at my legs to discover that I’m sitting right next to a giant hornets' nest. I slowly move away from the ball of swarming wasps, careful not to directly step on the nest. I’m able to walk away unscathed.

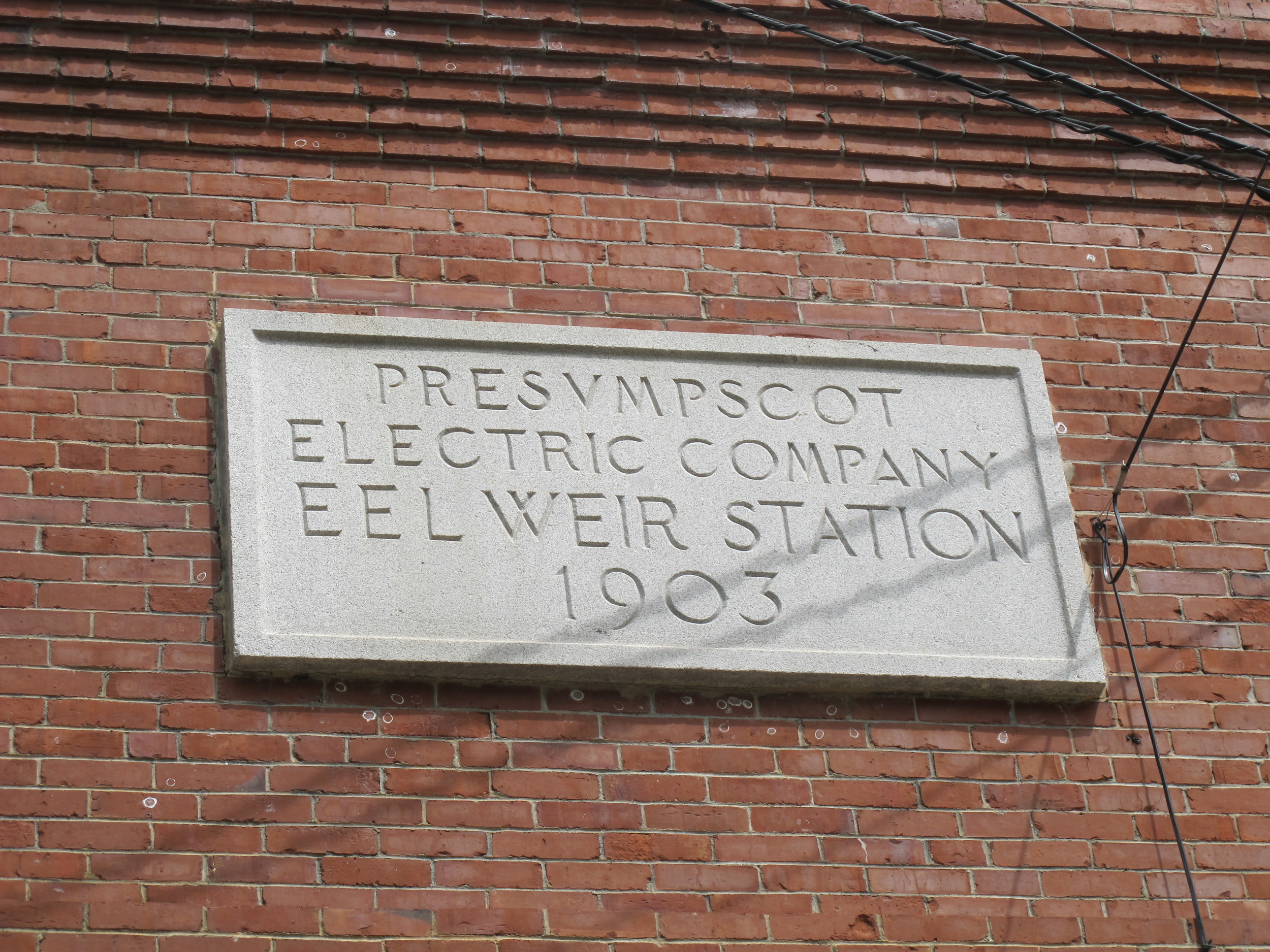

We drag our vessel up over the bank, and attach wheels around its stern to help in the difficult path to the next put-in, which includes traveling along Middle Jam Road where vehicles zoom by at 45 miles per hour. We bypass the Eel Weir Dam's old brick building whose plaque reads 1903. I realize it is this spot that has caused so much controversy regarding water levels.

At every portage on the Presumpscot bright yellow WARNING signs declare: “LARGE RIVER FLOW CHANGES MAY OCCUR RAPIDLY. FLOW CHANGES IN THE RIVER WILL BE PRECEEDED BY THREE BLASTS OF A HORN FOR YOUR SAFTEY. PLEASE RELOCATE TO THE RIVRBANK AT THAT TIME.” Because the basin feeds the Presumpscot the water levels of the lake directly impact activity on the river. The Eel Weir Dam controls those water levels and Sappi remains in charge of the dam. Sappi is a global company that operates a paper coating facility located on the Presumpscot in Westbrook and manages all of the river’s dams except for North Gorham (Great Falls). The company harnesses hydroelectric power for its business (not the public) but the amount is minimal—only about five megawatts total are generated from six hydroelectric dams.

Sappi must try to maintain specific flows throughout the year with mandates to keep Sebago Lake between 262 and 266 feet above sea level. They release water from the lake to the river at varying times, hence the warning signs. Their previous 30-year license for the Eel Weir Dam from the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee (FERC) expired in 2004, so the company is beholden to a provisional license while a new water management plan gets worked out. Brad Goulet, who oversees all of Sappi's dams on the Presumpscot, says the current plan (which was a compromise between several organizations and stakeholders) wastes water and disrupts natural flows into the Presumpscot.

I begin to notice that decisions concerning the river and lake have been made primarily with human needs and desires in mind, resulting in negative consequences for the environment. Sebago Lake is now nine feet higher than it used to be before the Eel Weir Dam. By altering natural flows so drastically many of Sebago’s long, exposed beaches are now underwater. Goulet explains that de-urbanization and the development boom in the 1970s and ’80s played significant roles in this shift, as the recreational motorboat business grew, and property owners desired attractive waterfronts. Sappi has proposed to change its management to allow for both high and low lake levels, depending upon seasonal rainfall and snowpack. The Portland Water District supports this decision, as they see no evidence that it would negatively impact the lake’s water quality. This would mean that at times throughout the year residents might have to walk out into muck as tides lower and recede from docks, which could be viewed as an inconvenience and an eyesore. The tourism industry might also suffer. But it would help stop the erosion of Sebago’s beaches and it would also provide more oxygen-rich water to the Presumpscot, thereby improving the river’s water quality.

After passing by Eel Weir Dam, Kyle and I follow power lines down an open path before cutting back into a patch of woods where no defined trail exists. Spotting a place that’s gradual enough for a canoe we jostle down to the water’s edge, stopping to rest for a few minutes and to eat some lunch, refueling with ham and cheese sandwiches.

I start to realize just how fragmented the river is and how much logistical planning is required to navigate trips from start to finish. Many locals paddle individual sections of the river but it’s not common for boaters to travel the whole river due to all of the portages. Thankfully, our canoe is durable and most of the remaining pullout spots are intentionally signed for public access. Kyle and I set off once again in our canoe and see the convergence below the dam where a little waterfall cascades down and we finally embark on the true Presumpscot.

Because of the many dams the river actually feels like a series of small lakes in several places as the water flattens out and slows. This holds true for the next section, identified as North Gorham Pond, below which is a small beach area where we decide to pull out and head home, marking the end to our first day on the river. My dad picks us up in his large utility van, and to our delight he has stocked a cooler with Stella Artois. After a tiring day of paddling, portaging, and struggling to find our rhythm in the canoe in hot summer weather, we eagerly embrace the cold beer.

Remnants of Days Past

We take a few days off from the river before returning to put in below Great Falls Dam, making our way to Dundee Pond. We pass by families splashing and laughing in the water and tanning on the beach at Dundee Park, and then we paddle underneath a covered bridge where kids use a rope swing to plunge into the water. Kyle points his finger and says, “Look!” as a blue kingfisher darts ahead of our canoe and flies from tree to tree, one side of the river to the other, like he’s showing us the way. As we follow his lead we approach turtles basking in the sun on top of rocks. When we get closer they plop beneath the surface and disappear beneath pink and white water lilies.

We continue downriver to Shaw Park, which opened in 2006 after Shaw Brothers Construction donated five acres of land to the Presumpscot Regional Land Trust in 1995. The park includes remnants of the old Cumberland and Oxford Canal, as well as the stone foundations of gunpowder mills that operated in the 1800s. Maurice Whitten, a former chemistry professor at the University of Southern Maine, has extensively researched the mill. In his book The Gunpowder Mills of Gorham-Windham, Maine, Whitten explains that Gambo Mill was the first powder mill built in Maine and was in operation longer than any other powder mill (about eighty years). The black powder consisted of saltpeter imported from India, sulfur imported from Sicily, and charcoal made from local Maine wood (alder, willow, poplar, and maple). The mills supplied a quarter of the gunpowder used by the Union during the Civil War and also supplied Russia during the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the Russio-Turkish War (1887-1888).

Both doctors and undertakers would ready their wagons upon hearing explosions in Gorham and Windham. Men ran towards the mill for two reasons: they were headed to help or they were looking for a job, because someone had most likely died. Gunpowder jobs paid much higher than others due to the risk involved—in the 1870s and 1880s workers made two dollars for a ten-hour work day, which was fifty cents to a dollar more than the going rate. Workers took precautions like wearing boots made with wooden pegs instead of nails to avoid sparks. Still, forty-six men ended up dying from explosions at Gambo, which changed hands several times and is most widely known for its ownership by the Oriental Powder Company (which changed from the G. G. Newhall Company in 1859). The Presumpscot Regional Land Trust has posted signs that indicate where the remnants of the old wheels are and where the charcoal house used to be located on an island on the Presumpscot.

While Kyle and I paddle down the river we continue to research its history and discover that in the years preceding gunpowder mills the Presumpscot supplied the first human inhabitants with a sacred resource, which has a somber story of disappearance—fish.

People of the Dawnland

As ships sailed into New England during the 17th and 18th centuries white settlers gobbled up land and Native tribes in Maine suffered devastating losses of major resources including fish, farmland, and firearms. Fighting frequently broke out among English, French, and Native peoples.

Along the Presumpscot tensions flared over dam construction that blocked fish passage, which the local Abenaki protested in myriad ways, guided by their outspoken leader Chief Polin. The Presumpscot supported a plentiful amount of Atlantic salmon, including both anadromous salmon, which fed in the ocean and spawned in the river, and non-anadromous salmon, which used Sebago Lake as their feeding area instead of the ocean. Other migratory species included American shad and alewives.

In 1735 the first dam appeared at Presumpscot Falls in Falmouth and in 1738 attempts to build a dam and sawmill at Mallison Falls (then known as Horse Beef Falls, located in south Windham below present-day Shaw Park) were foiled by Chief Polin and his tribe who sabotaged the settlers’ plans.

Because Maine was still part of the Massachusetts Bay colony, Chief Polin walked over a hundred miles all the way to Boston in 1739 to speak with Governor Jonathan Belcher about the dams and plead for fish passage for his tribe, which consisted of twenty-five men and their families. Massachusetts archives show that Polin explained to Belcher: “what we are most aggrieved at is that the River Pesumpscut (sic) is dammed up so that the passage of fish which is our food is obstructed, and that Colonel Westbrook did promise about two years ago that he would leave open a place in the dam and that the fish should have free passage up the river into the Pond in the proper season but he has not performed that and we are thereby deprived of our food.” Polin also requested that the English stop encroaching and settling upon his tribe’s land. Governor Belcher sent word to Colonel Westbrook to provide fish passage and said he would look into the matter of land ownership but nothing ever came of his promises.

Chief Polin was soon targeted as a major threat by the white settlers and a man named Stephen Manchester is remembered “heroically” in several local publications for his work as a Native American scout. In an 1896 account penned by Nathan Goold, Manchester is described as “a man of full six feet in height, sinewy and compactly built, very erect, with dark curling hair, a somewhat swarthy complexion, keen eyes and he probably weighed over one hundred and eighty pounds. He was calm and collected under all circumstances, a man of resolute courage and an adept in all manner of woodcraft.”

According to the account by Thomas L. Smith, on May 14, 1756 Stephen Manchester, Ezra Brown, Ephraim Winship, Abraham Anderson, Joseph Starling, Johnon Farrow, and four boys were walking through woods to work on Ezra Brown’s land. The local Abenaki tribe, armed with muskets, staged an attack. Brown was shot dead, while Winship received a shot in the eye and arm. Both were scalped. The fighting climaxed when Chief Polin fired at Anderson, exposing his location to Manchester, who fired and killed Polin.

Nathan Goold wrote, “The death of Polin brought peace and happiness to the border settlements, and of course the settlers felt grateful to Manchester for killing him. A tradition is that Manchester was offered a township for his reward but declined the offer saying it was ‘reward enough to have killed the skunk.’” Polin’s tribe carried him several miles into the woods and buried him beneath a young tree, which years later provided inspiration for New England Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “The Funeral Tree of the Sokokis”.

Having lost their leader, the Abenaki presence on the Presumpscot disappeared. The tribe seemed to have broken up, joining scattered bands from other tribes or else moving north, away from their homeland. Manchester went on to fight in the Revolutionary War before settling down at a small farm he built in Windham, and the town became more prosperous and populated. As the Native presence in the area faded the environmental problems rapidly increased. No longer fearing Chief Polin’s impassioned fight for fish passage, white settlers moved forward with their development plans. The river would forever be altered.

Hitting the Trail

Because of my interest in conservation work, on a morning off from canoeing I show up for a Stewardship Day at Great Falls Elementary School in Gorham, just down the road from Shaw Park, where a collection of trails lead to the Presumpscot on what is called the Hawkes Towpath Property. The event is put on by the Presumpscot Regional Land Trust (PRLT) as part of the statewide Great Maine Outdoor Weekend to encourage outside activities. Spotting a pick-up truck with PRLT’s signage, I walk over and meet the nonprofit’s new Executive Director, Stefan Jackson, and Board Member Don Wescott. The land trust was formed in 1986 to “conserve and protect natural lands and historic landscapes for posterity in the Presumpscot River watershed and western shore area of Sebago Lake.” In recent years it has expanded its outreach and increased its numbers, while sponsoring events, establishing land easements, and maintaining trails. On this morning a yellow school bus pulls up to the curb and middle school students hop out, led by alternative education teacher Heather Whitaker. After Jackson and Wescott explain what a land trust is and the importance of stewardship, the group walks into the woods bearing loppers and small hand saws to help trim overgrown limbs and bushes.

Heather Whitaker's class helps trim the trail. From left to right: Maia Puopolo, Nicole Williams, Haylie Morris, Teacher Heather Whitaker, Logan Fredericks, Teacher Lynn Smith, Mia Gallant, Jeremy Harmon, Justin Shiplet-Kilburn, Gabe Cousins, and Sawyer Hanscome.

Whitaker says that opportunities to get outdoors like this help teach her students life skills like cooperation, respect, and patience. I lead a group of energetic youngsters who have many things on their minds and my memory lingers back to my own junior high days when the world seemed smaller but nonetheless complicated. After the students return to their classroom Jackson, Westcott, and I walk again through the woods to discuss how to mark the trails better so that the loops are less confusing and the paths can become more defined.

The next day I continue to participate in the Great Maine Outdoor Weekend by joining up with a small group of hikers, led by Jackson, in walking a portion of the Sebago to Sea Trail, which began from initial efforts by the Presumpscot River Watershed Coalition several years ago and evolved into a collaborative effort between area towns and several organizations like the Portland Water District, Healthy Maine Partnerships, Portland Trails, and the PRLT. These combined forces successfully created a networked trail connecting Sebago Lake to Casco Bay, which parallels and includes the Presumpscot River in many places.

As we walk to the lake we discuss everything from current and past issues with the Presumpscot to broader themes about conservation’s role in town planning and community development. I decide to pay the annual $35 family membership fee so that Kyle and I can join the land trust because public spaces benefit from their hard work, and this is an opportunity to connect with like-minded people who care about the land where I am from. I begin to feel like this journey is the start to a much larger conversation that will continue for years to come.

Falling Towards the Rising Sun

As Kyle and I paddle down the Presumpscot he brings fishing poles and sends out casts. He is most successful in catching fish on an unseasonably hot day in September when we put our canoe in below Mallison Falls, just down the street from the Maine Department of Corrections in Windham. From the jail until before Saccarappa Dam in Westbrook nearly every cast he makes receives either a bite or else he hooks a bass. I immediately come to love this section as it winds behind farm fields, feeling more remote and peaceful than many of the other sections. We paddle by the Mosher family’s field where Kyle has worked for the past three summers picking and selling ears of corn at a farm stand on the corner of Mosher Road and Route 25. He’s been a friend of the family since preschool and the Moshers have long-standing ties to the community, as their ancestors were the third family to settle in Gorham. I helped Kyle pick corn this August for a couple of weeks and rediscovered that gratifying feel of manual work. Each morning the sun seemed to rise too soon and too quickly as we navigated the rows to crack stalks and peel back husks, checking for silk worms and proper germination before tossing the ears of Silver Queen, Incredible, and Mattapoisett into rubber bins, then heaving them onto the tractor.

The corn season has come to an end and the field will soon be plowed over so as our canoe drifts by we relish the stand’s memories and take a break from paddling to jump off a rope swing. We float with our stomachs facing the sky. A bald eagle soars overhead, circling once, before flying out of view.

Our feelings of ease and relaxation begin to fade as we approach Westbrook where the river most dramatically changes for the worse. Kyle and I notice a sudden change in the water. It becomes murky and stagnant and there are little to no signs of fish. We float by trash that has been disposed of in the river, which includes tires, old shoes, jars, and toys. A man who has brought his daughter to the river to feed the ducks asks if Kyle is catching any fish. When Kyle replies, “No” the man says, “It’d probably have three fins and ten eyes if ya did!”

As we paddle through downtown we look up at the towering white smokestack with faded lettering of SAPPI FINE PAPER vertically painted down its side, which serves as a landmark for the city. Before Sappi bought the mill in 1994 it was called the S.D. Warren Company and was the first coated papermaking facility in the U.S. as well as the second largest printing paper mill in the country. When my parents used to drive my sisters and I through Westbrook as kids we would plug our noses because of the mill’s foul smell. In 1999 the stench suddenly vanished as Sappi shifted from a pulp mill that produced printing paper to a supplier of release papers, developing texture for the coated fabric and decorative laminate markets.

Before the city received its name from Colonel Thomas Westbrook in 1814 there were two villages called Saccarappa (where downtown Westbrook now exists) and Ammoncongin (presently known as Cumberland Mills). Saccarappa is an Abenaki title meaning "falling towards the rising sun” while Ammoncongin means "high fishing place" and was the site of a two hundred acre cornfield for the Abenaki, who used fish for fertilizer. Following European settlement, year after year, the river became battered with untreated industrial and human waste. Lacking oversight, pollution soon encroached upon the Presumpscot. By the mid-1900s residents described the river as a dark-colored “root beer float”. It was thick with foam and reeked of a rotten odor. Its fumes peeled paint off of houses; its pollution killed fish and scared away community members. The 1967 Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game report states that by 1965 “S.D. Warren was discharging pollution amounting to 52,800 pounds per day into the Presumpscot. The City of Westbrook is daily contributing another 1,700 pounds of B.O.D. [biological oxygen demand, i.e., organic matter that uses up oxygen while decomposing] to the river.” By 1965 there was no measurable oxygen in the water at Blackstrap Road Bridge in Falmouth or Presumpscot Falls.

Needing to speak with someone who has firsthand knowledge of the river’s struggle, I’ve contacted an advocate named Will Plumley and he meets me next to the river in Westbrook. Plumley works in marketing but he possesses the patience and guidance of a teacher. He calmly explains that many people had given up hope for the river. He says, “In my lifetime this river was a total loss, a complete mess, just dead. Dead. A dead river. And something that people turned their backs on and walked away from—didn’t like the smell of it, avoided it.”

Plumley pauses to reflect upon his own connection to the Presumpscot. He grew up in Westchester County, New York and moved to Dayton, Ohio for a job before deciding he wanted to “settle in one place and live there for a long time and get to know it really well.” He felt “a sense of urgency in the early 1980s to figure out where that place was and get there.” A headhunter found him a marketing position in Maine so in 1984 he moved north. Plumley says he considers himself lucky for making his way to this state and to the Presumpscot. He saw a possibility in the river that many other people did not: a healthy future. So he studied woodlands management to best understand how to manage his ten acres of property by the river in Windham. He became a Founding Board Member of the Friends of the Presumpscot (for which he served as President for eight years), Board Member, Vice President, and Chair of the Marketing Committee for the Presumpscot Regional Land Trust, Chair for the Presumpscot River Watershed Coalition, and now sits on the Board of Directors for the Northern Forest Canoe Trail.

Plumley believes not enough emphasis or energy was spent on considering the natural world for issues concerning the Presumpscot. “I think we sometimes tend to look at things too much through the lens of human existence. We tend to evaluate options based on what’s in it for people rather than what’s in it for the larger system,” he says. For instance, dioxin standards are often measured by judging human health criteria rather than bioaccumulation (which focuses on the effects of the greater food chain, like if a big fish eats a little fish that ate a macroinvertibrate that had dioxins in it).

Becoming involved in advocacy efforts wasn’t necessarily easy for Plumley, as he admits, “Like most people I’m not fond of confrontation and conflict and yet I find that if it’s something I believe in then it’s not hard to [become] involved.” The organizations he has started and joined have created change by: pushing for the reclassification of sections once they improve (falling under A, B, or C standards); establishing water quality monitoring programs; promoting fish passage and dam removal; and generating public awareness. Years of persistence, hard work, and optimism from people like Plumley have literally brought the river back to life.

Not a Lost Cause

After several hours of searching, Kyle and I are unable to put in a canoe below the Cumberland Mills Dam at Sappi, as there is no public entryway suitable for a vessel. We admit defeat and move downriver to put in at a well-established spot at Riverton Park on a chilly morning in late September. When we untie the canoe from our truck and carry it to the launch I start to feel sad that this will be our last day on the Presumpscot. Even though I’ll continue to walk alongside its banks, I will miss the challenge of navigating by boat. The leaves are changing from bright green to red, yellow, and orange, and soon enough they will wilt to brown and die. It’s getting colder and a Maine winter is on its way. Snowflakes will descend, this water will freeze, and we will huddle indoors much more than we would prefer.

As the river crosses into the Portland/Falmouth region the trees along the river bend and sag. Their branches and roots reach out like unstable hospital patients looking for a cure, moaning in distress. Because of the many years of damming and logging the riverbank stabilization has diminished, making it much easier for sediment to impede the water.

In 1895 the Portland Railroad Company created an amusement park at Riverton complete with a casino, outdoor theater, and rental boats. A trolley serviced the park and steamboats called the Louise and the Santa Maria carried passengers between Cumberland Mills, Riverton, and Presumpscot Falls. I close my eyes and imagine the lively sounds of children playing and parents partying, along with images of parasols, cigars, and games of poker. Kyle and I paddle by an entire rusted-out car submerged beneath the surface, and I hear those noises and watch all of those scenes retreat to ghosts of the past. Then out of the corner of my eye I spot a fox standing on a cliff of bedrock above the Presumpscot. He sees our canoe and prances away into the woods. As the flash of orange disappears I recall the words of Frederick Matthew Wiseman, a New England scholar with Abenaki heritage who wrote, “My ancestors chose to stay and merge, in the eyes of the Anglo-Americans, with our French neighbors. Yet we kept our beliefs and customs. Other families took the Path of the Fox, to fade into the mountains and rivers seeing much and yet being unseen.”

Upon nearing the final portage Kyle and I hear a thunderous rushing of water. We notice the current is very strong. We pass a bright red sign warning of the falls ahead and start to worry that the pullout spot is too close to the edge. “Should we get out here?” I ask Kyle.

“I don’t know. We’re getting pretty close, those are the falls right there!” he yells.

Our canoe continues to swiftly glide downriver before we can make a decision and we immediately fear with this rapid flow that we might not have time to make it to land.

“There’s supposed to be a portage on the right but I can’t see any!” I yell back.

Realizing that we should have pulled out at the bank where the red sign was, we start to frantically paddle backwards, our arms becoming blurs as we fight the current. I start to think of “what if” scenarios, imagining the injuries and possible deaths that could result in our mistake. Then suddenly my brain kicks into survival mode, harnessing my nerves into energy in the form of deep, fast J-strokes. Luckily, I have Kyle leading the way who’s at least three times stronger than me.

We finally reach the bank and I start to feel relieved, but as soon as I step out of the boat I fall on my face. Our canoe is stuck on a slippery slope of clay known as the Presumpscot Formation—it’s a deposit of glacial marine mud that covers much of the coastal area in southern Maine. It has a bluish/gray color, clouds the water, and is susceptible to erosion. Both Kyle and I have to take our shoes off and walk barefoot, but it’s so slimy that I can’t even manage to stay on two feet. I resort to crawling on my hands and knees, feeling helpless and exhausted. Kyle somehow manages to grip his toes into the mud and heave our boat up the bank. We take a few minutes to catch our breath before lugging the canoe across a complex network of roots, having to rely on brute force because the wheels we’ve struggled to attach are useless on this terrain.

I’ve visited several waterfalls and rivers throughout the country. I’ve gazed up at towering Multnomah Falls in Oregon, which is over six hundred feet tall, and have seen a rainbow over and felt the mist of New York’s Niagara Falls. But as we turn the corner and finally see Presumpscot Falls, in this moment, for the first time, I see beauty in my backyard with a whole new understanding. It’s a beauty I’ve had to work to find. I can finally comprehend why the Presumpscot is called the River of Rough Places and I reflect upon the centuries of men and women who have tried to tame its rugged ways.

The falls have been revealed here because in 1996 a massive flood destroyed Smelt Hill Dam’s fish lift and several electrical generators. Central Maine Power, who owned the dam, sold it to the Coastal Conservation Association on account of the cost of repairs and the low amount of power it produced. The federal Army Corps of Engineers was called in to remove the dam and in 2002 the river once again ran free.

The removal of Smelt Hill Dam has marked the beginning of a new era for the Presumpscot, leading to a domino effect upriver. Last spring Sappi opened a fish ladder at Cumberland Mills Dam and FERC has also ordered Sappi to create fish passages at five other dams—Dundee, Gambo, Little Falls, Mallison Falls, and Saccarappa (Sappi appealed these decisions to the U.S. Supreme Court and lost). Groups like Friends of the Presumpscot are pushing for more dam removals.

Before Kyle and I head home I look back to this river I’ve come to know. It’s where I taught my golden retrievers how to swim, where I learned how to plant a tree, and where I first dared to jump off a railroad trestle into the water as a teenager. It’s a river that at times has been polluted, ignored, and controlled, but at other times has been loved, respected, and cared for. I realize why I ultimately needed to paddle this river in its entirety. It’s about commitment.

Maine is a state that’s pleasant to visit but demanding to live year-round. People have been abandoning this region for better jobs, land, and money since the general outmigration trend that began in the early nineteenth century. I was lured, like so many others, by dreams of westward opportunities. But in leaving home I came to appreciate all that I had left behind, including the struggle. I missed the raw weather and the informal dialect. I missed the communal underdog mentality. I missed the gritty aspects of the region as seen in the resilience of the Presumpscot River. Most of all, I missed the feeling of pride that comes with belonging to a place.

A Different Point of View

On a blustery day in November Kyle and I board a private plane piloted by our friend Sean Williamson to see the Presumpscot from the air. Having experienced all of the sections of the river on separate days of the canoe journey, I need to see the river from afar with a continuous view uninterrupted by portages. The Cessna quickly climbs and I glance out my window to the land below, its buildings and trees becoming smaller with each passing second. Williamson steers the plane over Sebago Lake Basin, then down past all of the landmarks that Kyle and I have paddled by these past few months. In setting off in the canoe I had gained access to a closer examination of the river—it afforded me the ability to feel like I could get to know it in a more intimate way. Now at a thousand feet in the air my perspective has expanded—I’m able to view how small everything seems and yet how connected this body of water is to the greater region.

I realize this is not just a story about coming home; it’s a story about finding home. It’s about sacrifice and compromise, understanding that the world is bigger than one’s own self and one’s own interests. That the effects of one fish or rock or dam or house along a river are not isolated or insular and that in order to create healthy communities filled with people who care about where they live there needs to be connection. There needs to be hope.

After our plane touches down on terra firma I return home and upload the photos from our flight. One picture in particular stands out. The foreground shows my small white house and in the background the Presumpscot River flows just inches away.